Piraeus

Viewing the city as a boisterous mosaic of multiple movements, encounters, arrivals and departures, the research project ‘100memories’ attempts to reconstruct fragments from the ‘biographies’ of four port cities. Our research aims to compose the cities’ biographies by selectively reconstructing the spaces, experiences, and transformations which shaped these port cities into places both distinct and distinctive, while at the same time firmly integrating them into a global history of movement.

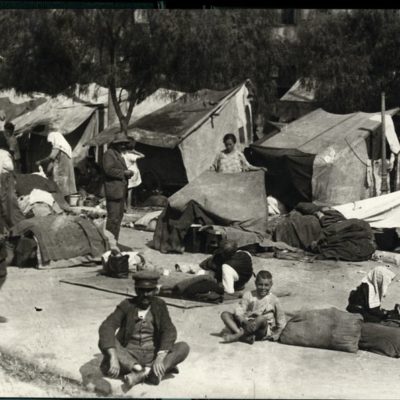

From September 1 to September 30, 1922, thirty-five steam ships and one ocean liner carrying more than 40,000 refugees from the Asia Minor coast docked at the Piraeus port and the neighbouring bay of Keratsini. Thousands of people disembarked in Piraeus and for days, weeks, or months, had to stay in expropriated accommodation, or remain homeless, sleeping in shabby makeshift sheds set up along the coastal highway and in churchyards, while new ships loaded with refugees arrived every day. As was true for most Greek port cities at the time, the endless refugee camp at the port and the city of Piraeus strikingly embodied the ‘refugee shock’ the Greek society had to grapple with after August 1922, when ‘a wave of mostly destitute refugees amounting to one fourth of the country’s inhabitants was added to the population’ (Christos Hadziiosif 2002, 9).

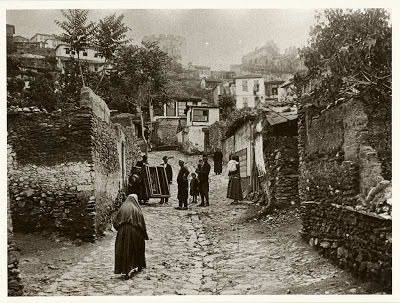

The imperative to find a comprehensive solution to the issue of refugee housing at the highest political level is clearly illustrated by the establishment of the Refugee Care Fund (TPP) in November 1922. One of the first tasks undertaken by the TPP was to conduct a topographic survey at the northern boundaries of the Municipality of Piraeus along the gully of Kanapitseri, in an area which would later become the southern part of the Municipality of Nea Kokkinia. As we read in the ‘Refugee Remembrance Journal’, by 1925, a ‘miracle of aesthetics, urban planning and public hygiene’ had taken place in Kokkinia, where 42,000 refugees from Asia Minor lived in a ‘vast settlement, a behemoth built out of patience, money, and technical knowledge’. The figures prove the truth of the matter: TPP had spent approximately 50,000,000 drachmas for the construction of 1,150 houses comprising 7,850 rooms in order to provide housing to Asia Minor refugees, mainly from Smyrna. A work force of 3,480 refugees worked on this housing construction project, among whom 759 were women.

On Monday, December 14, 1959, the ocean liner ‘Patris’ departed from the port of Piraeus carrying more than 1,000 passengers to Australia. After covering 9,500 miles, it arrived at the port of Fremantle 23 days later, on January 2, and at the port of Melbourne four days later. The signing of the bilateral agreement between Australia and Greece in 1952 signalled the beginning of the mass postwar migration wave from Greece. Within 20 years, more than 250,000 Greeks had settled in Australia and 3,000 in New Zealand. Most of the migrants were farmers and unskilled workers searching for better employment opportunities and life conditions than those of post-civil war Greece. Once again, the port of Piraeus became a transportation hub for people looking for work and striving for a better life. For most Greek migrants to Australia, choosing the country as their new homeland was a monumental life decision, since travelling back to Greece even on holidays remains to this day complicated and expensive.

On the morning of August 20, 2015, the ship ‘Eleftherios Venizelos’ docked at the port of Piraeus carrying 2,440 refugees mainly from Syria; 1,308 had boarded the ship in Kos, 124 in Kalumnos, 300 in Leros and 708 in Mitilini. This first arrival was followed by many ships chartered by the government to carry refugees from the islands to the mainland over the course of a few months. More than 1,200,000 refugees crossed the Greek territory during that time. Most of them had come from Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq to the Turkish coast, then to the Greek islands and from there, they arrived in Athens, Thessaloniki, Eidomeni and, via the Balkan route, Northern Europe. This period was characterised as a ‘refugee crisis’, but was also called ‘the summer of migration’. A huge wave of solidarity and support swept through the country at that time, with those who found themselves at the port of Piraeus experiencing both a terrible tragedy and an epic accomplishment and feeling conflicted emotions of joy and loss, hardship and hope, anguish and optimism.

Throughout this century, the port of Piraeus has constituted a place of arrival and departure, of goodbyes and reunions, but also a place of settlement for hundreds of thousands of people. The refugee neighbourhoods of 1922 later welcomed internal migrants from the islands and the mainland, bid farewell to those leaving for Australia, Germany, and Belgium, made space for migrants from the Balkans and Eastern Europe to build a new life in the 1990s, and showed their solidarity to the refugees who found themselves at the port of Piraeus in 2015, even if only temporarily.

Thessaloniki

Volos