Volos

Viewing the city as a boisterous mosaic of multiple movements, encounters, arrivals and departures, the research project ‘100memories’ attempts to reconstruct fragments from the ‘biographies’ of four port cities. Our research aims to compose the cities’ biographies by selectively reconstructing the spaces, experiences, and transformations which shaped these port cities into places both distinct and distinctive, while at the same time firmly integrating them into a global history of movement.

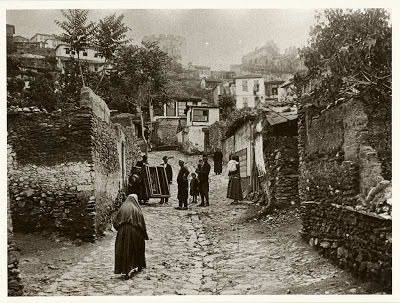

Throughout most of the 19th century, Muslims, Jews, Christians, Romani and ‘foreigners’ from Europe and elsewhere composed the diverse population of Thessaly. According to the 1881 census, when Thessaly became part of the Greek state, 90% of its population was Christian Orthodox, 9,1% was Muslim and 0,9% was Jewish. By 1881, many Muslims had already decided to leave Thessaly, as they didn’t wish to live in Greek territory. A period of instability, starting with the conflicts of 1878 and ending with Thessaly’s integration into Greece in 1881, led the Ottomans who lived in the cities of Thessaly to abandon the area. The Muslims of Volos left the city on November 2, 1881, when the Greek army entered the city, and never returned. As for the Jewish population of Thessaly, most of it was concentrated in the cities, with the largest community in Larisa (68%), followed by Trikala (20%) and Volos (12%).

When Volos was integrated into the Greek state, it was just a small town of barely 5,000 people. More specifically, according to the 1881 census, its population amounted to 4,987 inhabitants. Among them, there were 600 Muslims and 300 Jews. While the Muslims abandoned the town en masse after its integration, Jewish people continued to arrive in large numbers from different areas of Greece. By 1920, the Jewish population of the city comprised more than 2,000 people. Over the following decade, their number steadily declined and by 1935, it had dropped to 1,250, while at the outbreak of the Second World War, it was as low as 882 people. The first anti-Jewish measures were imposed by the German occupying forces in October 1943 and, in March 1944, 155 Jewish residents of Volos were arrested and sent to concentration camps where they were exterminated. From 1948 onwards, the remaining Jews of Volos migrated to Israel and the USA.

At the turn of the 20th century, both the city’s population and economy were growing. The population was rising steadily, from 4,987 people in 1881 to 11,029 in 1889 and 23,563 people in 1907. This increase can be mainly attributed to internal migration from the rural areas of Pelion and the mainland of Thessaly, as Volos was experiencing the first phase of its industrial development. It was over the first two decades of the 20th century that Volos also received its first refugee flows. Due to the conflicts throughout the Balkan Peninsula and Asia Minor, refugees from Eastern Thrace and Eastern Rumelia soon arrived at the outskirts of Volos. Some settled in the city, permanently or temporarily, while others founded refugee villages, such as Nea Anchialos in Magnisia, which was established by refugees from the Bulgarian town of Anchialos in 1907.

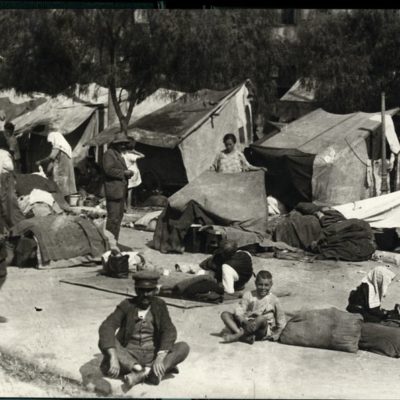

Between 1921 and 1924, a large number of refugees from the Greco-Turkish war of 1919-1922 arrived and settled in Volos (11,945 out of a total population of 47,892). Most of these refugees were employed as workers and it was their cheap labour that transformed Volos into one of the biggest industrial hubs in the country throughout the Interwar period. The city’s growing industry sector attracted people from the rural areas by promising them secure employment and urban life conveniences. The city of Volos remained attractive for rural populations throughout the first three decades of the 20th century, often presented as a place brimming with employment opportunities. After the Second World War and during the first two decades after the Greek civil war, men and women from the villages of Pelion and wider Thessaly continued to arrive in Volos looking for work. However, this internal migration towards the city was not exclusively driven by economic factors, but also by ‘forces’ associated with the particularly repressive political environment that was established after the end of the German occupation and remained dominant throughout the postwar period, not only in Volos but everywhere in Greece.

During the first decade after the Greek civil war, the labour market in Volos was mainly characterised by an explosive rise in unemployment, mainly due to a decline in production by the city’s major factories. Some Volos residents were forced to look for employment elsewhere, primarily in Athens, or in the industrial countries of Western Europe. However, the city barely participated in the major internal and external migration wave that was in progress throughout Greece at the time. One explanation is that in 1962, Volos was selected to host an industrial zone, ushering in a new period of economic growth and causing a major shift in the labour market.

At the beginning of the 1990s, migrants from the Balkans, mainly from Albania, settled in and around Volos. Since the city’s industry sector had shrunk significantly, these new residents had to find work in agriculture and construction, as well as in domestic cleaning and home care services. A similar route was followed by the refugees who arrived from the Global South and settled in various Greek cities, whether permanently or temporarily. In 2006, an accommodation facility for refugee minors opened in Makrinitsa, hosting about 25 young people under the aegis of the NGO ‘Arsis’. Later, during the ‘refugee crisis’, a refugee camp was created outside Volos on the premises of what used to be the ‘MOZA’ car dealership, while some refugees, mainly from Syria, were able to rent apartments in the city, supported by the ESTIA programme.

Thessaloniki

Piraeus