Thessaloniki

Viewing the city as a boisterous mosaic of multiple movements, encounters, arrivals and departures, the research project ‘100memories’ attempts to reconstruct fragments from the ‘biographies’ of four port cities. Our research aims to compose the cities’ biographies by selectively reconstructing the spaces, experiences, and transformations which shaped these port cities into places both distinct and distinctive, while at the same time firmly integrating them into a global history of movement.

During the 1990s, a language reappeared in Thessaloniki which had not been heard on the streets of the city for years. The number of Turkish-speaking, first generation Asia Minor refugees had been dwindling, but gradually, in markets, buses, and construction sites, Turkish could be heard again, as the Pontians of Tsalka, Georgia, who are overwhelmingly Turkish-speaking, started settling in Thessaloniki. This is just one of the many groups of people who moved to or from Thessaloniki during the 20th and the 21st century.

Since it was integrated into the Greek state in 1912, Thessaloniki has always been shaped and defined by population movements. In the decade between 1912 and 1922, masses of people moved to the city from Serbia, Bulgaria, Russia, Caucasus, Asia Minor, and Eastern Thrace. The Bulgarian community gradually moved back to Bulgaria, while Greek-speaking Vlachs from the area of Monastiri (Bitola) settled in Thessaloniki, along with Christian populations from Asia Minor, Caucasus, Bulgaria, and Eastern Thrace. A small group of White Russians found refuge in the city after their defeat from the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War. Several Christians returned to territories in Thrace and Asia Minor after 1919, while many Muslims chose to leave the city to settle in the Ottoman Empire.

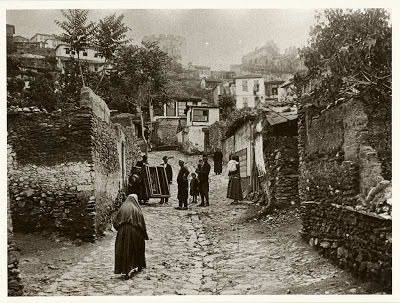

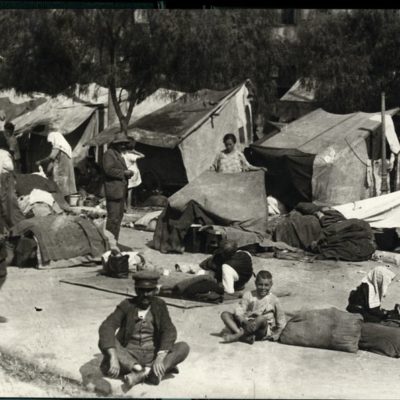

The Asia Minor catastrophe and the ensuing population exchange defined modern Thessaloniki. According to the first refugee census, which took place throughout the country in 1923, 88,612 people had settled in the city. Five years later, the refugee population of Thessaloniki had increased to 117,041 people, comprising almost half of the total population even before adding the significant number of Armenian refugees who had settled in the city. Thessaloniki grew and its centre was surrounded by refugee settlements, while simultaneously, the entire Muslim community moved to the Turkish state and Ano Poli, where they had mostly resided, was transformed into a refugee neighbourhood. Over the following years, part of the Jewish population, which used to be predominant in the city, migrated to Israel, the USA, and elsewhere.

If the arrival of Christian refugees defined the Interwar era, it was the extermination of the Jewish community by the Nazi occupation forces that finalised the total transformation of the character and anthropogeography of Thessaloniki, benefitting certain individuals and interest groups in the city. The extermination of the Jewish community was also symbolically sealed through its erasure from public space and discourse for decades.

The Greek civil war that followed the German occupation brought to the city the so-called ‘communist gang victims’, people who had been evacuated by the Greek National Army, who became the first seeds of a mass postwar internal migration wave. This migration reached its peak in the 1960s, significantly raising Thessaloniki’s average building height. Over the same period, many people from rural Macedonia, but even from Thessaloniki itself, migrated to Germany and other industrial countries of Western Europe.

After the fall of the military junta, but mainly after 1982, thousands of civil war political refugees were repatriated, with a large number settling in Thessaloniki. The regime change in Eastern Europe in the 1990s brought to the city populations from Albania and the countries of the former USSR (Georgia, Russia, Armenia), a large proportion of which were of Pontian origins. These populations were met with an inhospitable reception both on the social and the institutional level. At the beginning of the 21st century, population movements from Africa, the Middle East, and Asia to Europe brought new inhabitants to the city, some permanent, some on a temporary basis. The war in Syria caused these movements to peak in 2015. Eidomeni, Kilkis, just a few kilometres from Thessaloniki, became the site for the largest refugee camp in Europe which stayed operational for several months.

Today, in the area where Jewish refugees from Monastiri had established their synagogue, the only remaining synagogue in the city, other men, women, and children refugees go about their lives, their presence once again discreetly, but drastically, redefining Thessaloniki.

Piraeus

Volos